A German Love Letter

I have a knack for only appreciating artists once they have had enough from this life, and have decided to take a chance on what the next one has in store, either on Earth or elsewhere. Bowie was first, his unexpected death in 2016 sparking an unprecedented listening binge so I could try and work out the scale of what the world had lost. Genius is the short answer, not just for his records but for his imagery, constant reinvention, lyrical prowess and originality. But for the last year or so, it's not been Bowie who has guided my musical journey of life, but an eccentric band from Dusseldorf who have gone on to power so much of the music we appreciate today. It is Kraftwerk.

My first encounter with Kraftwerk was on a Soft Cell documentary I watched over New Year 2019/20. It was a fleeting reference, but I was intrigued by the minimalism and bold concept idea of Autobahn. However, upon first listening, I thought the concept initially outweighed the musical merits. It felt simplistic, and out of touch with the music I was familiar with, which was frankly the pop of the 80s, rock of the 70s, and the occasional Noughties 'banger' I heard at a party, back when they were a thing.

I wasn't helped by Spotify. Algorithmically programmed to show me the 5 most popular songs, I found myself listening to tracks from different albums from vastly different periods and in very different styles. I can still remember the order the songs were in. First up was 'The Model' by far the most streamed song, perhaps because it was a pop song, released as a single multiple times and even reaching No. 1. Next was 'The Robots', a track from the same album but going in a different direction, an unsettling voice synthesiser removing any emotion that could be deduced from Ralf Hutter's frustrated yearning in 'The Model'. Then came 'Autobahn', the 22 minute track taking up the entire A-side of their eponymous album. Frankly, I didn't know what I was listening to, or why on earth Hutter and co-founder Florian Schneider had decided to write a tribute to perhaps one of the dullest modes of transportation known to man. Then came a re-mastered 'Tour de France' which arrived with a strange panting noise that I reacted to as perhaps anyone listening might. Finally, came 'Radioactivity', the lead track from the first album after 'Autobahn'. An interesting song but its mixture of English and German lyrics made it difficult to understand the concept behind the track. Over the coming months, riffs stayed in my head, and I tried to grapple with why on earth this band were seemingly criss-crossing oddball topics with such a seeming void of emotion. Bizarrely intrigued, I decided to investigate further.

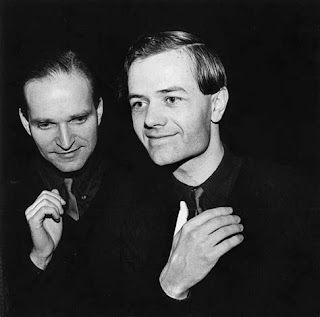

But just as I was starting to listen to their albums in full, news came through in May that Florian Schneider had died of cancer. The outpouring of appreciation and tributes surprised me, given their distinctly moderate and uneven commercial success. Soft Cell, OMD, even David Bowie's estate paid tribute. Reading the numerous obituaries and tributes gave me a stronger sense of what I'd been missing.

Kraftwerk were formed in the aftermath of the West German protests of 1968, a time when German music lacked an identity of its own. Hutter and Schneider began by playing experimental 'krautrock' - a genre that included NEU! (made up of early Kraftwerk members) and CAN (a band so left-field that their lead singers eventually quit - one through a nervous breakdown, another to become a Jehovah's witness). Yet out of the increasingly avant-garde nature of krautrock, Kraftwerk began to move away to an increasingly electronic sound. In fact the release of 'Autobahn' was the last Kraftwerk album to feature any 'conventional' instruments, with the band's 1975 appearance on Tomorrow's World introducing them to a broad, otherwise inaccessible audience.

***

Right, I'm getting bogged down so I'll try and explain myself. I adore Kraftwerk. They're perhaps my favourite band at the moment and they have been for a few months now. 'But why?' I hear you heckle. 'You didn't understand them until a few months ago and now you just can't get enough?!' All of that is true, but Kraftwerk have come to encapsulate much more than a jingly melody here and there. Kraftwerk not only foresaw major technological developments of transportation and the internet, but also significantly contributed to the forging of a new 'international' German identity, free from the tarnished brush of war, and instead promoting an industrialised, advanced, and even sardonically humorous nation.

After the release of 'Autobahn', Kraftwerk settled on a consistent line-up that would last for their most productive decade. With each passing album, Kraftwerk would examine a technological development and how it could change the world as we understood it. 'Radio-activity' took on the dual focus of growing communication and the powers and perils of nuclear energy - a contentious topic at the time. 'Trans-Europe Express' referenced the growing European integrationism that was promoting a Kantian vision of peace after decades of conflict. 'The Man Machine' offered a critical perspective on urbanisation, consumerism and the rise of artificial intelligence, the latter expanding on the ideas of 'Showroom Dummies' from the previous album. In my opinion, the strongest album as a whole is 1981's Computer World, which surprisingly accurately predicted the rise in Information Technology and government intelligence services. Creative difficulties then stalled the band's next album, with the band themselves being overtaken by many of the technological developments they had been among the first in music to introduce. 'Electric Cafe' eventually arrived and failed to impress critics, creating a long period of inactivity, with only a remix album to show for the following 17 years.

I'm still stalling why Kraftwerk have impacted me the way they have so here goes. I guess I take great comfort from their musical stability. Hutter and Schneider are not deities sent to Earth to forewarn us of the dangers of what is to come, they are artists. Artists who wanted to break free from the legacy of Nazism, and shape a unique musical path for their own sake. Both men have shunned publicity throughout their lives.Yet their lyrics, and their music, are constant sources of comfort. The rhythm of the drum machines, the definite, even at times soothing nature of the electronic sounds that aren't shaped by human error, are delightful to listen to. I feel immensely enriched by being able to understand Kraftwerk's context and relevance in each album, not on a Spotify list. As much as I would adore a new Kraftwerk studio album, a first for nearly 18 years, Kraftwerk have spent most of that time constantly remastering, remixing and, in particular following Schneider's departure from the band in 2008, touring, taking an ever more refined sound around the world. But lyrics are perhaps what also do the band justice.

Overall, though there are worthy exceptions, the English-speaking music I listen to is rhythmic, it can make you dance through the room, sing to the top of your voice, or tap your feet. Older French music is lyrically powerful. Introspective, you can empathise with musicians living in a world completely different to your own. When not trying to imitate Anglo-pop, French music moves me in a way so inarticulate, it pains me that I can't explain further. Yet for me, Kraftwerk seem to go further. By setting lines of hope and despair, to melancholic riffs, their abstract concepts of urbanisation and technological developments feel somehow relevant. I have in particular found great comfort and pain in many tracks since moving to Edinburgh.

'Ohm sweet Ohm', the closing track of 'Radio-Activity', is a slow track that carries your mood and lifts you as it progresses. When first moving to Edinburgh, home sickness lingered to the point where it merely pissed me off, not because anyone is for a minute suggesting you up sticks and return, but simply because you are away from home. But I played 'Radio-Activity' in my room, and this final track initially reflected the sinister pain of being far from home and friends before gradually reminding me of life outside the 4 walls of my room in the flat. These reminders came not from lyrics, but from the melodies.

'Neon Lights', similarly, is my song for when I stand on Calton Hill at dusk and look out at what is supposedly my city, and remark at how vastly grander it is than the suburban monochrome of Solihull. The lyrics, simple but repetitive are both intimidating and warming, set to a synthesised flute that evaporates my worries and lowers my heart rate to that resembling a hibernating groundhog. Or it is for when I'm carrying heavy shopping through the Meadows and turn to look back down at not only at where I've been, but how far I've come. I reflect that this now represents my life going forward, in this city which at the fall of night is made of light. The long Scottish winter nights make this track particularly apt, it is perhaps my favourite.

Or maybe it is 'The Telephone Call' a track from 'Electric Cafe'. As bizarre and slightly dysfunctional as that album was, it spawned a beautiful 7 inch single release of this song which spends the verse reminding me of the pain and struggle of being far from home, not being able to hug a loved one, before gorgeously reminding me of the power of communication of the modern age. Never suggesting that the latter could ever equate the former, it still serves as a reminder that I'm never alone. I remember walking through Grassmarket late at night, annoyed with myself for a mildly unproductive day and another lonely night staring at the TV screen. Yet this song came on and I froze, goosebumps coming over me just as they are now writing this.

***

The disadvantage of returning home is two-pronged. There is the initial sense that everything is slightly smaller than you remember, that things are irretrievably different once the free world has chewed you up for a semester - even during a pandemic. Then there is the gradual retreat into the person you once were, the person whose persona you gradually shed across University, before picking up the pieces and returning home to refamiliarise yourself with home life. It is a comfort blanket, your heart telling your head that you'll always be yourself, just that some things will perhaps never change and you can always fall back on who you used to be. It's a painful delusion, one that reared its ugly head when leaving home after Christmas.

I didn't worry for myself as much as I worried for who I really was. Am I my own person, or do I find myself just variously floating or grinding through life, my personality being bashed and cracked into shape by wherever I am and whoever I meet? I also worried for my mum, who had to recalibrate once more what life without her son around would look like. I wanted to tell my mum a lot when I left, I wanted to say that I could always give her my affection and time, even if it meant getting a connection on the telephone line, rather than tea across the table. Sometimes I wanted to confront the reality that we're so close, yet far away, in an age where we can talk to anyone from anywhere, yet we cannot feel one another's presence. In the end, all I could say on the doorstep, suitcase in hand was that I would call her up from time to time, to hear her voice on the telephone line. It was a sucker punch of a Kraftwerk lyric, one which in that situation, did not need the corresponding melody.

Music means different things to different people, but to me it is a soundtrack of life. When I hear music I am transported to where I have been, where I wish I had been, and sometimes where I wished I wasn't but appreciated retrospectively. Over the last year, I have listened to Kraftwerk's music for what it is, a series of abstract concept albums. Yet they not only portray such innovative electronic complexities as simple nuance, but also cautiously predict how the future would end up - not just technologically, but also musically as people from Madonna to Jay Z to Depeche Mode would testify. One of these days I'm determined to see them live, when my immense gratitude to the publicity-shy artists can be expressed through cheers and applause. That is if the cheers won't be drowned out by the drum machines and synths...

Kraftwerk simultaneously transport me to where I'd never thought imaginable, mentally and physically. They are ambient, yet never vacant. Upbeat, but never gleeful. I'm also reminded when I listen to them, that in a world of certain change, Kraftwerk at least saw some of the change coming, and to me, that brings unquantifiable relief.

***

I've not usually felt the need to add citations to posts before, but for this one, I'd like to reference Uwe Schutte's book about 'Kraftwerk: Future Music from Germany' which I got for Christmas and devoured in 2 days. I strongly recommend!

Comments

Post a Comment